‘If you never fail, you're not being stretched’: Embracing the art of the possible, with scientist Susan Greenfield

Want your little girl to believe that anything is possible? Then take her on a guided tour of the thrillingly multifaceted life of Baroness Susan Greenfield, scientist, broadcaster, author and CEO extraordinaire.

Glamorous, funny, and tirelessly innovative, Greenfield could be described as the Madonna of science. But labels imply limits, whereas she blazes with the energy of someone for whom transcendence is the rule, not the exception. Although frankly, rules don’t interest her.

Few people are better qualified to discuss resilience, the joys of style and how to nourish children’s imagination in the digital age. After years as the BBC’s poster-woman for science, today she leads a pioneering biotech start-up that may lead to cures for Alzheimer’s, cancer and – yes! – wrinkles.

How does she do it? ‘It’s about living life from the inside out.’ And also prancing around to Abba, as often as possible, as well as playing Barbies with her honorary goddaughter, Maria.

First things first: do we address you as Professor or Baroness Greenfield?

The only place I’m called Baroness is – sarcastically – in Australia. Susan is fine!

What advice would you give your younger self?

Not sure. You know that famous quote by Martin Luther: 'Ich kann nicht anders': 'I can't do otherwise'? I’ve always done what interested me and followed my nose.

Today your chief focus is Neuro-Bio, your biotech start-up. But you’re no starched-and-suited CEO. After years as a researcher you came to fame via broadcasting.

It all started in 1994 when I was the first woman to deliver the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures, which were televised on the BBC. That’s what gave me an appetite for it. The general public were so grateful compared to cynical students!

And then you went on to become the first female Director of the Royal Institution. The consistent thread throughout your career is a refusal to accept limits being put on you. What and who inspired you?

I always loved performing but I didn’t have pushy parents. My dad was an electrician and left school at fourteen, although if he had been born at a different time, he would have been a philosopher or an engineer. Mum was super bright and won the county scholarship to my school, Godolphin and Latymer. But everyone was very snobby to her because of her working-class background, laughing because she had cardboard soles in her shoes and so on. It got worse when they were evacuated during the war, taking her out of her comfort zone. So she ran away, joined the Sherman Fisher Girls Chorus and went on the stage.

The huge advantage of my parents was they were the right combination of monumentally supportive but they let me do my own thing. So when I came home and said I want to do A-level Greek it was, ‘Oh, that’s nice dear.’

Also, my brother came along when I was thirteen, so effectively I was an only child, and they thought I was the most wonderful thing in the world!

So you were spared the halitosis of anxious parents, hovering over your homework. Instead your mother fed your passion for glamour and performance.

Up to a point. As a child I loved looking at old photos of her in her dancing clothes. But when she married, that was the end of her career, so when she found out she was pregnant she hoped I would be a girl and take up where she left off. And as soon as I could walk, I was into ballet classes. I loved the showing off, the clothes and the make up, but although I was passable at dancing, I was hardly Darcey Bussell. However, I loved reading. And although Mum was a bit perplexed, it says a lot for her and for Dad that they let me find my own way. And because I liked reading, I was very dreamy; in my own little world, making up stories, and always, always asking questions.

You didn’t study science at sixth form, beginning at Oxford University with Philosophy. So how did you switch to science?

If there’s a running theme to my so-called intellect, it is, what makes a person a person? What is a mind? And of course that was touched on in Greek philosophy. But I soon got disillusioned with the university course. Mostly, it was formal logic and, having done maths A Level, that was a cakewalk. Also, the linguistics! I remember sitting in the Bodleian Library, reading an article on the definite article – on ‘The’. Can you imagine?

But Classics gives you great intellectual confidence. If you can do Greek grammar, which has no logic whatsoever, you can do anything. So I changed to psychology, despite having no science credentials. My tutor, a lovely woman called Jane Mellanby, said, ‘Go and see this Professor in Pharmacology’ – she thought it would be a hoot! So I went and he asked me a question that was essentially the scientific equivalent of ‘Do you know who Shakespeare is?’

And I said, ‘Frankly, no.’

'Ah, well,' he said, ‘you can tell us about Homer in the coffee breaks.’

What enviable freedom.

I liked the insouciance. They let me have my head and try. If you fail you fail. Like my American boss said many years later, if you never fail, you’re not being stretched.

You went into science not understanding the rules.

That was a great bonus. It was like the Emperor’s New Clothes – I challenged dogma all the time. But I never woke up one day thinking, ‘I want to be a research scientist.’ I always wanted to find out things and be myself. It never crossed my mind to try and shoehorn that into some kind of career. It never felt like I had to comply.

Like many brainy women in the public eye, people often get very excited about the fact that you care about your appearance, as if this were odd. Still, I have to ask: are you wearing red lipstick?

Lip stain today. My eyelash extensions need doing!

And you still have a dancer’s legs.

I used to play squash three times a week but I discovered running in lockdown.

Starting out, did you feel you had to present yourself in a certain way?

No, I’d never wear boring clothes to appease someone else. I always dressed in my own style, such as it was – I liked vintage 1930s dresses and Oxfam charity shop finds, inevitably, because I had no money.

I used to get lots of comments – still do. ‘You scare men.’ Or ‘You don’t look like a scientist.’ And other women being bitchy, of course. But you just roll with it. You know who your real friends are. You know you haven’t done anything wrong. So you have your own moral compass. And if people don’t like you, that’s their view. It comes down to resilience.

You’ve written about how digital media encroaches on childhood. How can we preserve its magic?

If I could give you any advice as a parent it’s that all of us in life have problems – if you didn’t, you’d be pretty boring. So the thing is to enable a child deal with it.

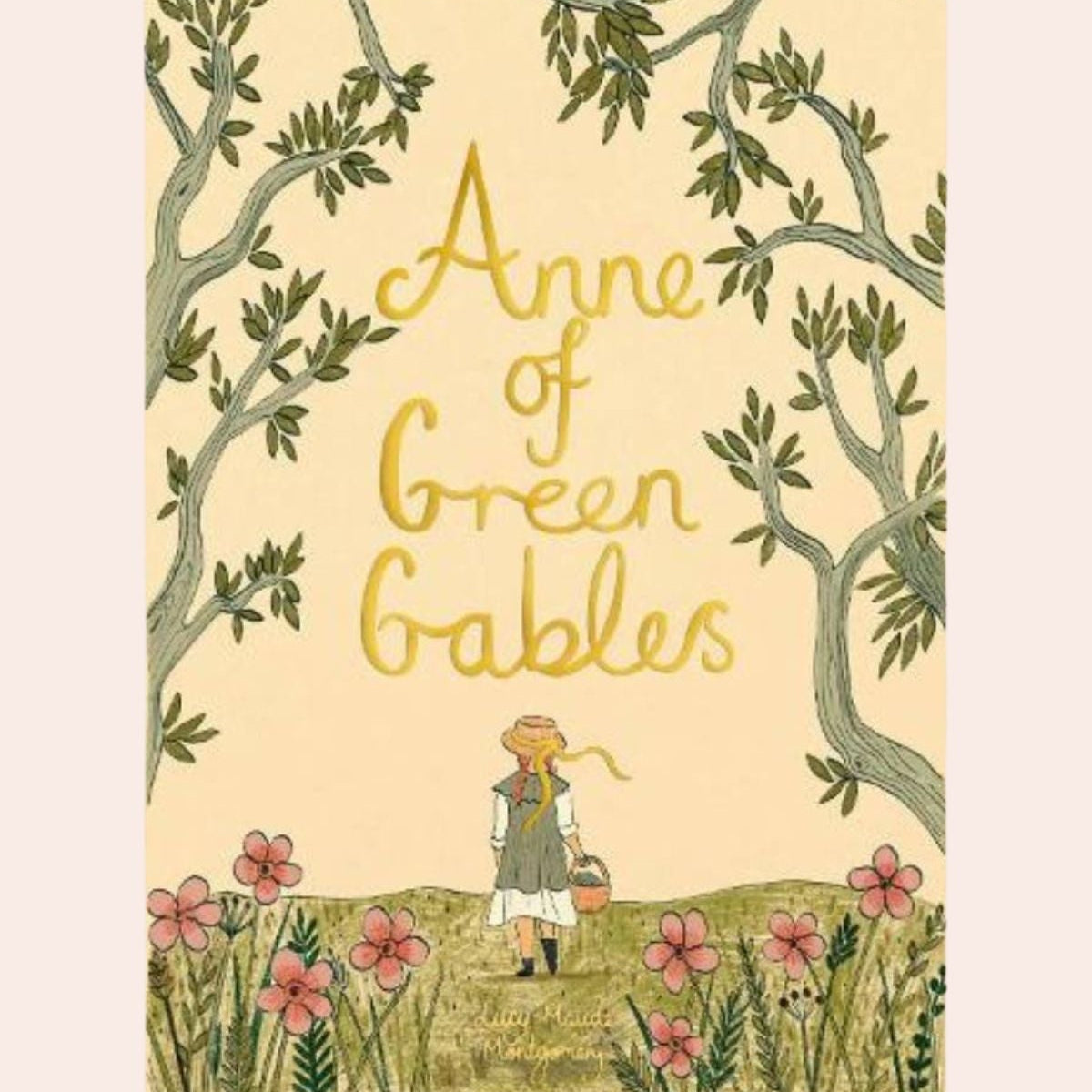

How can we build resilience? With imagination. Firstly, read to small children. Because when you read, rather than look at a screen, you go to a place beyond your immediate physical senses. This encourages imagination, a longer attention span, and the development of an inner world – I’m very into inner worlds. I still remember in my kindergarten, gripping stories of Baba Yaga, the wicked Russian witch with metal teeth who ate the heads off children. She became my role model for when I babysat my brother!

Secondly, give kids time and encouragement to make up games and stories. That’s the magic! The games come from nothing, and they belong to them.

Lastly, lots of exercise, because that improves cognitive skills.

Imagination prevents them from being a passive receiver.

I remember meeting a guy, a guru in Silicon Valley. He said, ‘I grew up in Africa with nothing. My five siblings and I played outside all the time. But my son has every toy he could want, every luxury. And I wouldn’t swap my childhood for his.’ Which begs the question: why give all the toys? Imagination won’t grow if your child is bombarded with images made by someone else.

Are we scared to let children get bored?

Being bored is the secret! As a child I was completely bored. We had no money, and we lived in Chiswick! There was only the library, drawing pictures or going for walks. But being bored, you create your own stimulation – from the inside.

Today there’s too much emphasis on being a brand: how people perceive you, how you come across, rather than what you’re feeling yourself. It’s part of the obsession with recording the minutiae of our lives.

There’s a drift to living life from the outside in.

Exactly. You need to live life from the inside out. To develop a narrative: your own life story.

What’s your main focus today?

Neuro-Bio. It’s a small biotech company with a uniquely innovative approach to Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s presents one of the biggest challenges of our time. Yet nothing much has happened [in terms of a cure] because scientists are very conservative, often adopting variations on the same theme. But what you need is a paradigm shift. It’s no good just looking at things in the brain of post-mortem Alzheimer’s [patients] and seeing, for example, amyloid and targeting that. What we need is a theory.

So our company asked something new: what is special about the brain cells that die? And we believe we’ve discovered a basic developmental process that, if errantly triggered, causes Alzheimer’s. And we’ve thought of a way to intercept that process. This insight lends itself to three products pertaining to Alzheimer’s, and two more. Because cancer is a form of inappropriate cellular development, so we have an oncology asset. And there’s also an application for skin aging too.

Will you keep us young and beautiful?

Yes! But our drug is streets ahead of the other assets. In spring last year we commissioned a lab in Verona to test its ability to improve memory. Now this was the epicentre of the Covid outbreak in Northern Italy, but fortunately they were able to continue. And although there was every reason why this experiment wouldn’t work, it did! So now we’re moving to the regulatory stage. It’s very exciting.

Words: Catherine Blyth

Photos: Ulla Nyeman

M&H: Jo Gillingwater

Digital Operator: Katie Rollings